Why Lilly's Derica Rice Isn't Your Typical CFO

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

Derica Rice isn’t what I expected.

Honestly, not having interviewed many pharma company CFOs, I wasn’t sure what to expect. However, from the little I did know about Rice, the CFO of Eli Lilly and Company, I knew that an in-depth discussion of complex financial strategies or the kinds of detailed analyses found only in a company’s annual report wasn’t what I hoped he’d talk about. I wanted to know more about what it takes to be a CFO in this industry these days. What kinds of decisions is he faced with? What business strategies does he struggle with, and how does he overcome the challenges of this demanding position? Basically, I wanted to know what made this guy tick. Luckily, he didn’t disappoint.

An Unusual Tenure

There are a few facts about Rice that are not only atypical of a Big Pharma CFO but also warrant further exploration. First, he has spent his entire professional career — 26 years — at Lilly, including a role as a pharma rep. “I remember meeting Jim Cornelius [Lilly's CFO from 1983 to 1995] back in 1990 when I was interviewing, but at the time I really didn’t know what a CFO did,” Rice says with a chuckle. Those days in field sales may be long in his past, but his experiences during that time forged an appreciation for this business function that he still cultivates in his current role. For example, he occasionally will go on territory field visits and even attend field sales meetings. “To understand the daily challenges they are facing, I need to hear what is on their minds,” he says. “If, as a senior leader, you take the approach that you don’t have time or are too important for a field sales ride along, not only are you missing the challenges and problems that are out there, but you also will be blind to many emerging opportunities.” But it’s not just the field group that he stays connected with; he spends time with the R&D team, talking to Lilly scientists and learning what they are trying to accomplish — and what he can do to help.

Another fact about Rice that makes him unique in this industry is also tied to his tenure at Lilly. His 10-year run as CFO outpaces the average tenure of a CFO at a Fortune 500 company by four years. That’s impressive on its own, but it’s even more significant when you consider that he’s held this position without having an accounting background. Oh, and don’t forget that he has served on Lilly’s executive committee longer than all but one of his leadership peers — only CEO John Lechleiter has served longer. In fact, it was a meeting with Lechleiter in early 2013 that led to one of the most unusual and interesting facts about Rice.

An Unexpected Challenge

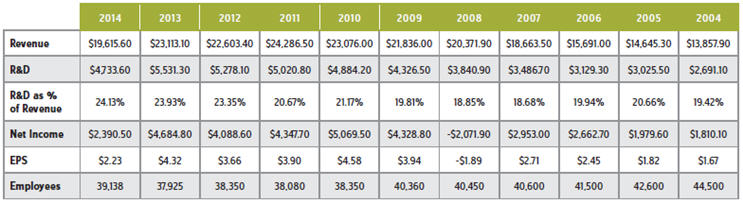

As Rice recalls, the one-on-one meeting had been scheduled well in advance, so it wasn’t unexpected. The company had just closed the books on 2012, a year punctuated by declines in just about every key financial performance metric except for how much it had spent on R&D (see table 1), so the CFO obviously had a lot on his mind.

“I walked into his office with my typical to-do list,” Rice recalls. “As I got through bullet points one and two, I could see John was becoming a little impatient.” Undeterred, Rice continued his review. After a few more minutes Lechleiter interrupted and said, “That’s not what I need to talk to you about today.” The CEO then explained that he needed to have surgery for a dilated aorta. “He was very matter of fact about letting me know that he was going to be out for a while,” Rice states. “But when he said that he wanted me to step in and serve as interim CEO, I heard the words, but at the same time … I didn’t. It was a lot to process.”

To an outsider, the decision probably seemed logical. After all, Rice was a longtime Lilly employee and even had been CFO for the two years prior to Lechleiter being named CEO (see “Different Leaders Face Different Challenges”). Naming him interim CEO was also in accordance with the company's bylaws, so it really shouldn’t have been a surprise that the board of directors agreed to the then 48-year-old Rice serving as interim CEO.

Still, in that moment, Rice’s mind was awash in the enormity of this news. “You have to understand; I grew up in Decatur, AL, with very modest means,” he reflects. “We weren’t poor. We were po. The difference between poor and po is that when you are po, you are so poor you can’t even afford the last o and r!” The oldest of seven whose father died of a stroke when Rice was just 11, he and his siblings were raised by his mother, a type 2 diabetic who provided for the family by working as a school custodian.

He says those humble beginnings have helped him stay grounded during his career, which is a personality trait that is especially useful when you’ve been suddenly tapped to be the CEO of a 140-year-old pharma giant — even if it was for only 68 days. But Lechleiter and the board’s faith in Rice during this time indicates the kind of versatility that a pharma CFO needs to exemplify these days. In other words, the job goes well beyond that of merely directing corporate fiscal functions.

TABLE 1: 10 YEARS OF ELI LILLY & CO. KEY PERFORMANCE MEASURES

(Dollars in millions, except per-share and employee data)

Preparing For Years YZ

Beyond his field sales experience, Rice served in various management positions that helped give him the versatility he would later need as CFO. For example, in 2004 he was the head of the company’s global planning organization when a generic manufacturer challenged the patent validity of Lilly’s Zyprexa (olanzapine), an antipsychotic generating $2.5 billion annually at its peak, that wouldn’t go off patent until 2011. “My job was to put together a contingency plan in case we prematurely lost the patent,” he explains.

Though Lilly was successful in upholding its patent, the experience gained from the planning process proved very fruitful. Rice says it helped the company determine what elements of the business Lilly would want to leverage in order to endure such a patent expiration scenario. In particular, this meant pursuing an innovation-based strategy.

The patent loss time period spanning 2011 to 2014 was referred to at Lilly as “years YZ.” When Rice took over as CFO in 2006, he was immediately thrust into solving the problem of how to survive and prosper throughout those years. “We decided to double down on investing in R&D,” recounts Rice. “We weren’t going to do large-scale mergers to finance and engineer our way through such a scenario. We weren't going to diversify into noncore biopharma areas such as consumer products or generics. And, we weren’t going to cut R&D spending by 30 or 50 percent as a means of financially traversing the anticipated revenue gap.”

He explains that the plan was to figure out how to improve R&D productivity and quality, increase pipeline output, and then rebase (i.e., improve and reduce Lilly’s cost structure) the company. “We wanted to take the hits from the patent expirations but then begin growing the company, albeit off a smaller starting base.” (As table 1 illustrates, Lilly consistently increased investment in R&D, as either a dollar amount or as a percentage of revenue.)

Decision Making Amidst The Noise Of Naysayers

Of course, when you’re talking about the financial strategies of a publicly traded pharmaceutical company, you’re bound to be inundated with naysayers. Indeed, when Lilly first announced its R&D philosophy, there was an abundance of outsiders who were quick to second-guess this strategy. Rice says that skepticism only fueled the company’s desire to further validate whether this was the right path for Lilly. “We didn’t discount those opposing thoughts, views, and comments; we fully considered them,” he says.

Rice and the executive team looked across the industry for examples of companies having successfully managed their way through this type of serious patent expiration without taking “some fairly draconian action, including changing their strategy.” Other companies had chosen to go the M&A route. For example, shortly after Lilly announced its R&D strategy, Pfizer purchased Wyeth. About a month later, Merck said it was acquiring Schering-Plough. “A lot of our management team felt that Merck and Lilly were very similar in our commitment to R&D, and here they were choosing a very different route than what we’d chosen. Then, another of our competitors announced they were cutting R&D by 20 percent,” Rice adds. “Still, I can’t say that we second-guessed our decision.”

The company did a lot of contingency planning during this time. Rice says the goal wasn’t to confirm that they were right about their decision but to determine how wrong Lilly could be and still be OK. “The goal was never perfection, because trying to put together the perfect plan would be a flaw in and of itself,” he says. Throughout the contingency planning and testing, the one fact that consistently became apparent was the overwhelming importance of R&D over the years to the company’s success. “With every challenge we have faced — whether it was Oraflex [Lilly’s arthritis drug linked to toxic reactions in the 1980s], Clinton administration healthcare reform, or product patent expiration — it was our R&D innovation and our ability to bring new clinically differentiated products to market that brought us through these tough times. We decided that was something to focus on since it was within our control.”

How A CFO Drives Company Focus

As CFO at the time, Rice’s role was to drive that focus and prioritization and help the company navigate the tradeoffs that are inevitable with such a plan. For example, all of the company’s business segments were narrowed down to five — bio-medicines, diabetes, animal health, emerging markets, and oncology. From there, the company looked at the human health therapeutic areas that seemed to have the best opportunity (e.g., neurodegeneration, oncology, diabetes, autoimmune, pain). “We then built our R&D efforts on these, determining which specific molecules within each therapeutic category we wanted to pursue,” he explains. “We had to determine how we would resource these molecules, and for those not selected, decide if we were going to shelve them for later or discharge them altogether.”

Rice admits that getting through the YZ period required a great deal of discipline from himself and the entire leadership team. After all, despite all their planning, not everything went off without a hitch. When they started the YZ race, eight of the first nine late-stage molecules in their pipeline failed. “It was a bit of a surprise that not only taught us about our level of determination but also the importance of execution, the need for continuous improvement, and that getting through all of it would require the entire team,” he states.

Rice may not be your typical pharma CFO, but I’m guessing Lilly's long-term investors are OK with that. The road is littered with carcasses of companies that took “typical” approaches to hiring leaders and solving problems. Sometimes success resides in atypical leadership.

The Employee Challenges Of A Looming Patent Cliff

The patent loss time period spanning 2011 – 2014 was referred to at Lilly as “years YZ.” Though the dreaded patent cliff would hit the balance sheets of many big pharmaceutical companies, the reality is that Lilly was due to be one of the hardest hit. “When I became CFO in 2006, the initial crux of my job was to begin cultivating plans and strategies for how we would manage our way through years YZ,” explains Derica Rice, Lilly's CFO.

The patent loss time period spanning 2011 – 2014 was referred to at Lilly as “years YZ.” Though the dreaded patent cliff would hit the balance sheets of many big pharmaceutical companies, the reality is that Lilly was due to be one of the hardest hit. “When I became CFO in 2006, the initial crux of my job was to begin cultivating plans and strategies for how we would manage our way through years YZ,” explains Derica Rice, Lilly's CFO.

The first challenge was to get the organization to pay attention to a series of events that wouldn’t take place for another three to five years. That was especially difficult considering that in 2007 the financial forecast for Lilly looked pretty favorable, having just closed the books on its best year ever (i.e., $3 billion increase in annual revenue). But Rice and CEO John Lechleiter knew that preparing for the pending storm would require more than 6 to 12 months of preparation. “It would take years to put things in motion,” Rice attests.

The second challenge was to prevent employees from losing sight of the present. “We still needed good performance in the near term,” Rice says. “Though you are trying to get the ‘pending storm’ message to resonate, you don’t want people running for shelter three years too early.”

Different Leaders Face Different Challenges

When Derica Rice was named CFO of Lilly in 2006, he joined John Lechleiter as a member of the executive committee. At the time, Lechleiter was functioning as the company’s COO. But this wasn’t the first time the two had worked together. “I had the opportunity to work with John before he became the COO,” Rice explains. “When he was the president of our global pharmaceutical business and head of what we used to refer to as our product teams, I was his CFO. It was then that I really got a sense of his approach, philosophies, and leadership style.” While this may have been Rice’s first opportunity to work closely with the CEO, as it turned out, it wouldn’t be his last.

History has shown that turnover at the CEO position at many companies often doesn’t bode well for other members of the senior leadership team. But when Lechleiter replaced Sidney Taurel as CEO in 2008, one of the constants through the transition was Rice. Being one of the few Lilly executive committee members to have served in his current position under both CEOs, Rice has a rather unique perspective on both leaders, as well as the challenges each faced. “As you can imagine, their styles were very different, and that's to be expected,” he says. “But the business circumstances were also very different. When Sidney [Taurel] was in the role, we had come on the heels of the Prozac [fluoxetine] patent expiration.” The blockbuster antidepressant that was first launched in early 1988 received numerous additional indications that extended its patent into 2001. As a result, the extremely successful selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) ended up generating approximately 30 percent of Lilly’s total revenue during its life span. “We had launched a series of new products under Taurel, and the company had gotten to a pretty good growth trajectory,” Rice reflects. “But as John was looking to take on the role of CEO, he wasn’t facing the patent loss of one product but four of our largest products representing about 40 percent of our revenue.”

The antipsychotic Zyprexa (olanzapine), generating $2.5 billion annually at its peak, would go off patent in 2011. In 2013 the company faced the loss of not one but two drugs (i.e., Humalog [insulin lispro injection] and Cymbalta [duloxetine]) with a combined annual revenue of $7.4 billion. Finally, in 2014 Lilly would lose the $1 billion revenue generated by its osteoporosis treatment, Evista (raloxifene). “How do you lead a company through such a series of patent expirations, rebuilding that base, and still continue to have an ongoing entity?” Rice asks. “It required a different leadership style, approach, and focus.”