Winning Management Strategies For Early And Late-Stage Drug Development

By Carolina Ahrendt

What does strategy look like for a drug development program? The word strategy can mean different things to different individuals. If you polled a group on a development team, you may receive different strategy definitions and differences in what it means to be strategic.

Ask a CEO, and they’ll state their corporate strategy, such as mission, values, culture, business plan, and pipeline of products. Ask a functional lead, and they will likely state the strategy from their departmental lens (i.e., clinical, chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC), nonclinical, or regulatory) with a roadmap or approach to achieve a desired outcome and benefit to patients.

Let’s look at this closely. For regulatory, the strategy could be to submit the Investigational New Drug Application (IND), but along the way, the strategy could be to have a couple of FDA interactions such as an INTERACT or Pre-IND meeting prior to submitting the IND, or positioning information in the sponsor rationale of the meeting package to achieve a particular outcome and push the boundaries to see what may be acceptable to the FDA.

But ask a program lead or manager, and they think of strategy in a holistic and integrated way for the development program. That’s because program managers have insight into the cross-functional strategy and tactical plans, and the corresponding impacts to the overall program.

Still confusing? Well, let’s start with the basics and frame the strategy with its counterparts of tactical and operational activities to make the comparison.

When people think of strategy, tactical and operational team members find it easier to understand the difference through a comparison:

- Strategy: Reflects corporate mission, while developing a product development roadmap from discovery to launch to benefit a subset of patients.

- Tactical: A translation of the strategy into an action plan, such as an integrated development plan.

- Operational: Encompasses day-to-day activities ensuring tasks are carried out efficiently and effectively.

Now that we have a clearer understanding of the definition of strategy, the strategic needs for a program are multi-faceted since considerations come from a combination of functional and corporate insights. Each functional strategy feeds into the integrated program goals and involves stage gates or inflection points that potentially drive the following corporate goals: acquire additional funding or resourcing, increase the value of the stock price, inform a press release, or engage a potential partner during due diligence, with the goal of partnering or purchasing. Thus, a program strategy is dependent on the business strategy as well as the technical program goals.

Stages Of The Drug Development Lifecycle

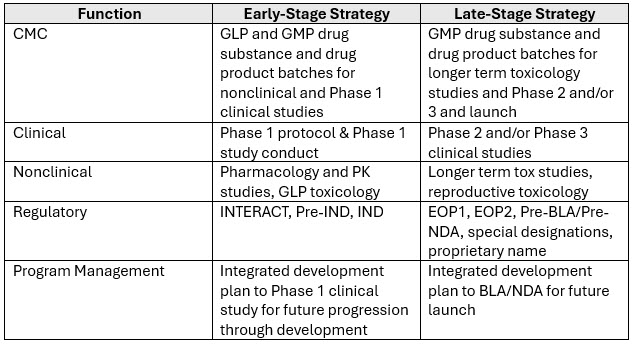

In the drug development life cycle, stages of early and late-stage development are defined as the following:

- Early-stage development: Preclinical essential work is complete, a drug candidate is identified, and the drug is ready to progress to a clinical trial.

- Late-state development: Data is collected from a clinical trial with the intent of filing a marketing application and obtaining FDA approval.

Ultimately, the strategy for end-to-end drug development requires a team of subject matter experts, including program management and leadership roles. Unfortunately, functional areas often believe that development strategy is the province of clinical or regulatory teams, but that approach and mindset misses the big picture.

While I certainly recommend a drug development strategy from the long-game perspective — thinking beyond just early or late-stage milestones — I also recognize that it is not always feasible. So, here are a few considerations for early- and late-stage development strategies.

Early-Stage Development Strategy

Early-stage development is the point where a development candidate has been identified based on specific biological and chemical properties and is ready to move into clinical development. The strategy here is multi-factorial, since the goal is to start the Phase 1 clinical trial, and to do so, the passport to entry is the IND application containing activities related to CMC, nonclinical, and clinical.

From a business perspective, the corporate goal is usually speed to IND. For example, there is a focus on the regulatory strategy and experiments to enable the IND, and the planning involved to begin the clinical trial. From the program perspective, this means evaluating strategies from various cross-functional areas. From the regulatory perspective, this means considering whether an INTERACT and/or a Pre-IND meeting with the FDA is needed and what topics to discuss at each of the FDA interactions, since they enable a successful IND submission and ‘study may proceed’ letter. Then, the developer can begin conducting experiments, preparing reports, and summarizing the information for the IND application. From the nonclinical perspective, this means determining which studies help to clarify the mechanism of action and the animal studies to determine the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) properties and doses based on a no observed adverse event level (NOAEL) calculation for a toxicology study. From the CMC perspective, this means evaluating the properties of the drug candidate and going from lab scale-up to larger quantities, and formulation development to optimize the transport or vehicle for delivery to the patients. From the clinical perspective, determining the CRO selection, leveraging relationships with KOLs or investigators in the field of study, site initiation visits, data management, safety monitoring plans, and enrolling patients into the study is all essential.

The program management perspective is to pull all these activities into an integrated development plan, while understanding the costs and resources. However, they must include activities and information from earlier in development process, as it relates to the competitive landscape, setting up the infrastructure for reports to show compliance, exploring other country options in case enrollment cannot be done solely in the U.S. or just at one site, and once clinical data is available, which conference should this information be presented at per the publication plan.

Late-Stage Development Strategy

As the drug progresses, the focus shifts to clinical development and filing a marketing application such as a Biologics License Application (BLA) or New Drug Application (NDA). Strategically, late-stage development could have different outcomes for the companies. This is where the clinical data remains the determining factor that can make or break a program depending on the results of the pivotal study. Imagine being successful in early-stage clinical trials and then getting to your pivotal study or a Phase 3 study that is costly and getting results that do not meet the endpoint or are not superior to a standard of care or comparator?

From a business perspective, the corporate goal is usually to obtain clinical data, and along the way, engage with the FDA to understand future approval strategy and readiness for the BLA or NDA submission.

From the program perspective, the development activities are more advanced. What do I mean by this? There are many functional activities running together. For example:

- Nonclinical program includes longer duration toxicology studies (13 weeks instead of a 4-week study and additional reproductive toxicology studies, if applicable).

- Regulatory program includes special designations and additional end-of-phase meetings with the FDA to get their feedback on the next study design or planning for success with a future BLA or NDA.

- Clinical program includes evaluating the product in even more people to show the magnitude of the effect on special populations (elderly, renal or hepatically impaired).

- CMC program includes producing Process Performance Qualification (PPQ) batches or registrational batches for long term stability or shelf-life.

- Program Manager takes all of these elements to build an integrated roadmap for a future marketing application approval (BLA or NDA).

The program management perspective is to pull all these clinical activities and stage them for marketing application readiness. Additional key considerations include inspection readiness activities, evaluating whether to file a marketing application in Europe or other countries concurrently or in a staggered manner, commercial readiness for launch, and/or raising additional funding or due diligence to partner with another company to share the costs and workload.

Program Management And Leadership Strategies

To propel the strategic drug development vision into reality, there are skillsets and approaches from a program management perspective that are essential to the program’s success. Let’s look at the strategies employed by a program manager and how their leadership abilities change or adapt to add value to a drug development program.

In drug development, program management and leadership are often associated with the operational aspects of drug development, but there are strategic elements in this role that are critical to maintaining the vision and the critical path to development. Such strategic elements could include finding a new mechanism of action, hunting for a drug candidate that shows better characteristics compared to competitors, trying to maximize regulatory designations to reap the benefits of faster approval, or running multiple clinical studies to show clinical benefit, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, or properties that are more superior in a patient population compared to the standard of care.

A program manager is the liaison and driver of the program, understanding the regulatory landscape, requirements, and the critical path. Some claim to know the critical path, but I am not sure it is well understood.

The steps enabling late-stage development work should not be overlooked in the early-stage, however, it is still essential to understand the differences in strategic approaches depending on the development phase, while also remaining flexible and nimble as clinical data may adjust the strategy as development progresses. This is why it’s crucial to have a program manager and/or leader to champion the program from a wholistic perspective as they integrate the functions to align with the overall corporate goal, and inform executives about scenarios, when necessary, if changes are needed for the benefit of the business and program.

The myopic view of compartmentalizing early and late-stage development strategies from functional departments is becoming a way of the past. It’s time to meet a more modern development approach, integrating functional plans to the business goal, otherwise, we risk a lack of understanding dependencies and changes impacting the critical path. Why does this matter? Your budget and timelines will take the hit.

About The Author:

Carolina Ahrendt is principal consultant and program leader at Halloran Consulting Group. She is a thought leader and SME in life sciences program leadership and management.