Arbitration For Pharmaceuticals?

Congress is wrestling with two major health policy issues this summer: “surprise medical bills” and prescription drug pricing. Legislation is advancing through congressional committees on both these issues. But the concept known as “arbitration” to resolve billing disputes between out-of-network providers and insurers on surprise medical bills could spell doom for the pharmaceutical industry if it is crosswalked into the prescription-drug debate.

Congress is wrestling with two major health policy issues this summer: “surprise medical bills” and prescription drug pricing. Legislation is advancing through congressional committees on both these issues. But the concept known as “arbitration” to resolve billing disputes between out-of-network providers and insurers on surprise medical bills could spell doom for the pharmaceutical industry if it is crosswalked into the prescription-drug debate.

Both of the issues are fueled by populist ire over high or unexpected medical bills experienced by patients. There is bipartisan consensus that Congress needs to act, and President Trump has committed his administration to enacting legislation this year on both issues.

In developing health policy, Congress tends to borrow ideas from other arenas (e.g., states or different healthcare sectors). Some of the leading proposals to address surprise medical bills would borrow from New York’s 2015 law based on baseball-style arbitration, which has been very effective in resolving disputes between out-of-network providers and insurance companies.

Major League Baseball’s arbitration process settles salary disputes between players and teams by requiring the player and the team to both offer an appropriate salary and an arbiter selects one of the two offers. This has forced both parties to make more reasonable offers for fear of the other’s offer being chosen.

Likewise, New York has seen a “dramatic” decline in consumer complaints about balance billing: “It’s downgraded the issue from one of the biggest consumer concerns [the Consumer Service Society’s call center] receives to barely an issue,” said one regulator. And very few cases make it to arbitration because both parties understand what the arbiter is looking for. A Georgetown University study on New York’s process has found that decisions that have been rendered are roughly evenly split between providers and payers.

Congress is now contemplating federal legislation that would replicate New York’s baseball-style arbitration for out-of-network providers. This is the preferred solution for physicians and hospitals that complain that the alternative of setting prices at a median in-network rate in the geographic area would tip the scales toward insurers (many of which dominate certain regions) by allowing them to simply reduce their payment rates in subsequent contracts.

IMPLICATIONS TO THE PRESCRIPTION DRUG DEBATE

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) has been floating arbitration as a solution to bring down the price of prescription drugs. The concept presents a clever repackaging of the more fundamental policy goal of the left: government price controls over prescription drugs. While we have yet to see paper delineating the details of a proposal, the speaker’s staff has publicly stated they are considering subjecting anywhere from 25 to 250 drugs to binding arbitration in Medicare, with the progressive caucus demanding even more.

Medicare’s Part D plans presently negotiate with pharmaceutical manufacturers on price, rebates, and formulary access. That system has worked; recent data published by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission shows that Part D costs have been flat from 2015 to 2017 (holding steady at about $80 billion), even as other health costs have increased. If a Part D plan fails to effectively negotiate with manufacturers, that will be reflected in higher premiums, and it will lose market share as seniors can choose other more cost-effective plans.

Medicare’s Part D plans presently negotiate with pharmaceutical manufacturers on price, rebates, and formulary access. That system has worked; recent data published by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission shows that Part D costs have been flat from 2015 to 2017 (holding steady at about $80 billion), even as other health costs have increased. If a Part D plan fails to effectively negotiate with manufacturers, that will be reflected in higher premiums, and it will lose market share as seniors can choose other more cost-effective plans.

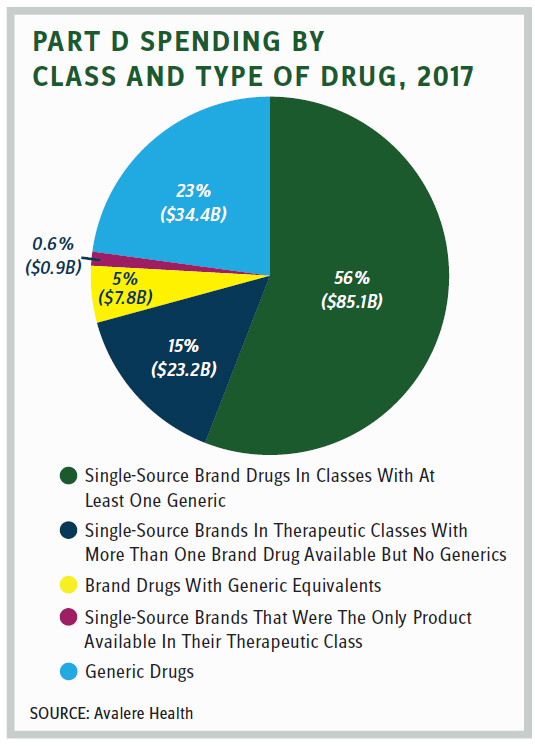

But proponents of arbitration in Part D counter that plans have little leverage to negotiate with manufacturers that have a single drug in a therapeutic class. Yet how pervasive is that phenomena? An Avalere study released in June found that “The majority of 2017 Part D spending on single-source brand drugs was in U.S. Pharmacopeia classes that included other generic or brand drugs. Less than 1 percent [$0.9 billion] of total Part D spending was for single-source brands that were the only product available in their therapeutic class.”

And what would be the effect of such a pricing scheme focused on first-in-class drugs, where there is the most unmet medical need?

More importantly, is New York’s arbitration model for out-of-network providers, which is meant to settle disputes between two private parties (the provider and insurer), the appropriate model for determining prescription drug prices in Medicare?

In Medicare, the arbitration would be between the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (the government) and the pharmaceutical company (a private party) with the arbiter being another agent of the government. Two-on-one does not seem to be a recipe for fairness to the private party. Failure to accept the result means the drug would not be covered, and the manufacturer and patient would lose.

Indeed, arbitration has led to impaired patient access in countries that have employed such schemes. For example, in Germany, which uses arbitration, only 71 percent of new cancer products are available compared to 96 percent in the U.S. Setting the price too low results in shortages, a concept learned in most Economics 101 classes.

DETERMINING THE VALUE OF INNOVATIVE PHARMACEUTICALS

Baseball is a notoriously statistics-driven sport where number crunchers compare players on a plethora of known and detailed, quantifiable variables. Michael Lewis’ “Moneyball” describes how statisticians now drive player acquisitions over the old-school techniques that relied on scouting reports. Player agents and teams are unlikely to make a mistake of greatly misvaluing a player. In contrast, determining the value of innovative pharmaceuticals, particularly if they are first in class, is much more complicated.

How the Trump administration views binding arbitration for prescription drugs remains an enigma. The president seems to pride himself on his negotiating skills, first becoming notorious with his book, “The Art of the Deal.” But negotiating a deal to improve seniors’ prescription drug benefits and ensuring privately negotiated price concessions reach patients would be far preferable to establishing a price-setting process sure to result in greater government control over the industry whose yet-to-be-developed innovations stand to do the most to improve patient care for the foreseeable future.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.