Election Fallout: Can Divided Government Forge Bipartisan Solutions?

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

November 4 — Several things we can conclude from the still unfolding election returns:

November 4 — Several things we can conclude from the still unfolding election returns:

- Pollsters are about as obsolete as a Blockbuster Video rental card.

- The nation remains deeply and almost evenly divided — there is not an electoral mandate for whoever wins the White House.

- Republicans are likely to hold the Senate, and the blue wave did not materialize despite an avalanche of spending by Democratic challengers. A Republican Senate will block most liberal initiatives.

Vice President Biden proposed sweeping plans to remake how healthcare is delivered to Americans, including a new “Public Option” government-run insurance that would undermine employer-sponsored commercial insurance. Healthcare providers (e.g., hospitals and physician practices) rely on that private delivery of healthcare to offset poor payments from Medicare and Medicaid, and a government-run plan would have quickly gained market share and threatened their economic viability. However, a Public Option plan cannot advance in a Republican-controlled Senate.

Similarly, with a Republican Senate, Democrats cannot jam through their pharmaceutical price-control bill that sailed through the House twice on a party-line vote. That bill would have crippled the pharmaceutical industry by not only slashing prices in public programs to mirror those in price-controlled countries but entitling commercial payers to those same prices as well.

Democratic staff and policy experts in liberal think tanks had spent much of the summer plotting the enactment of several “budget reconciliation” bills designed to pass on a 51-vote majority (as opposed to 60 typically needed to overcome a filibuster) that would have massively hiked taxes on the wealthy and corporations as well as defunded the pharmaceutical industry in order to finance healthcare coverage expansions. Those presumptuous plans are now in the trash bin.

Instead, Congress has an opportunity to forge bipartisan consensus on more incremental approaches to healthcare policy. Perhaps it can start with legislation that was reported on a bipartisan basis early last summer in the committees of jurisdiction to restructure the outpatient Medicare drug benefit and limit patient out-of-pocket costs?

That would be a welcome change in approach from the fixation on international reference pricing. The industry should be a working partner with policymakers in developing solutions that reduce their patients’ economic duress and enhance adherence to their medications.

What About the Staggering Budget Deficit?

But as the political parties fought out controversial issues in the raucous campaign including healthcare, taxes, immigration, and police reform, one issue remained totally absent from the national debate: the nation’s staggering debt.

That’s unfortunate because there is a cresting wave of debt that threatens to swamp the country and deserves focus from the new Congress and president.

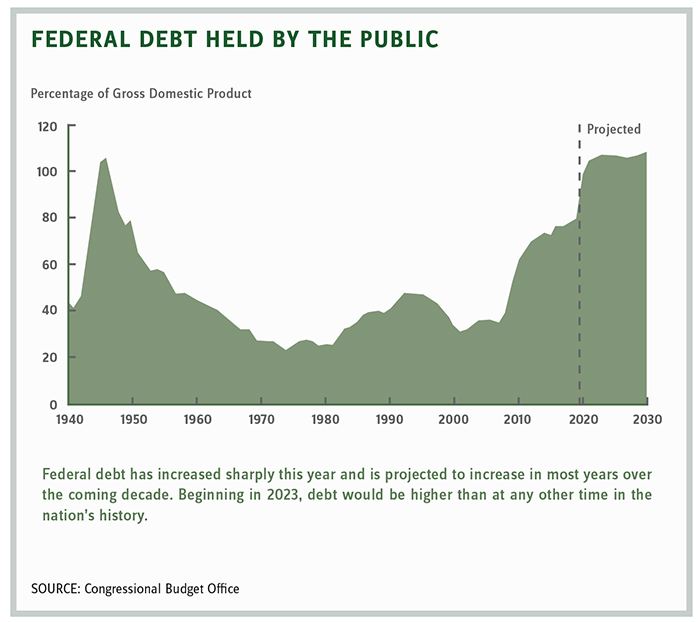

In September, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its mid-year report showing the nation’s finances had collapsed during the pandemic. CBO projects a $3.3 trillion deficit in 2020, triple that of last year and $2 trillion more than was projected in March 2020. At 16% of GDP, the deficit in 2020 is the largest since 1945, when the U.S. was borrowing to win a two-front world war.

While CBO projects yearly deficits to gradually decrease to 5.3% of GDP by the end of the decade, they eclipse the 50-year average of 3%. And the accumulated debt from years of massive deficits will approximately equal the size of the economy this year. That always has been considered a tipping point.

Just as troubling, annual interest payments on the debt are projected to rise from $375B in 2020 to nearly $1.4 trillion in 2030. Those are resources that can’t be used for more productive purposes, including infrastructure, education, healthcare, and national defense.

Neither presidential campaign presented any serious plan to deal with the crisis. Vice President Biden’s laundry list of new taxes on the wealthy — massive payroll tax hikes, repeal of the Trump tax cuts to marginal rates, new taxes on capital and limitation of deductions — would have simply funded new programs. And by most estimates, the taxes would fall far short of the wide-eyed plans to implement elements of the Green New Deal, make public college tuition free, and expand healthcare programs. Similarly, President Trump provided no real plan to bring the chronic and expanding deficits under heel.

This fiscal profligacy is not supported by most Americans. A poll commissioned two weeks before the election by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation found the vast majority (94%) believe it’s important for the next president to pay for priorities so that they don’t increase the federal budget deficit once the pandemic is over. More than half favor a combination of tax increases and spending cuts to reduce the deficit, with a minority of voters favoring solely spending cuts or solely tax increases.

Unfortunately, the focus appears to be enactment of a fourth COVID relief package that can cost trillions of dollars. In May, the House of Representatives passed a $3.4 trillion package that including everything from a $1 trillion bailout of state and local governments to healthcare for illegal aliens. The Republican Senate responded with a more targeted $500 billion package, but President Trump indicated he was ready to support a package of $1.8 trillion. Election season politics scuttled an agreement, but the issue will be back on the table even before the new Congress is sworn in.

Certainly, the federal government’s primary responsibility should be stabilizing markets and providing critical assistance to out-of-work and suffering individuals and small businesses during a pandemic. But when deficits are structural and an ongoing reality of a country at full employment, significant reform of the nation’s fiscal house is in order.

No party operating by itself can take the political risk to make the tough decisions necessary to right-size the scope and reach of government. But a new Congress with divided government can offer the opportunity for members of both parties to share in the political risk to forge bipartisan consensus on these long-term problems that have been ignored and grown unchecked for too long.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.