Impeachment Halts Health Policy Advancement As Coronavirus Spreads

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

As the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump dragged into the latter half of the second week, the wheels of healthcare policy development have ground to a halt. The Senate trial opened with the Sergeant at Arms admonishing members “to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment.” Typically verbose senators accustomed to spinning dramatic arguments at committee hearings (often angling for a moment that may go viral), have been forced to sit silently at their wooden desks for hours at a time and listen to seemingly endless, redundant arguments by the impeachment managers and White House counsels. The rules, intended to focus the senators on their duties as jurors in the trial, prohibit access to cell phones or consumption of any liquid other than water or milk.

As the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump dragged into the latter half of the second week, the wheels of healthcare policy development have ground to a halt. The Senate trial opened with the Sergeant at Arms admonishing members “to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment.” Typically verbose senators accustomed to spinning dramatic arguments at committee hearings (often angling for a moment that may go viral), have been forced to sit silently at their wooden desks for hours at a time and listen to seemingly endless, redundant arguments by the impeachment managers and White House counsels. The rules, intended to focus the senators on their duties as jurors in the trial, prohibit access to cell phones or consumption of any liquid other than water or milk.

While the Senate Judiciary hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh elicited throngs of angry and animated protestors who descended on the Capitol last fall, the impeachment trial of President Trump has left the halls of Congress almost entirely vacant. A lone protestor with a handlebar mustache stands outside the Hart Office building with a homemade sign: “U.S. out of Iraq!” The president’s vocal opponents and spirited MAGA hat-wearing supporters have apparently opted to stay home, perhaps because they have been told that the Senate’s verdict is preordained.

The halls of nearby congressional office buildings remain eerily quiet. A young legislative assistant walks her golden retriever through the second floor of the Senate Russell building, with the clicking of the dog’s toenails on the marble floor echoing down the empty hallway. Committee rooms, normally boisterous with rancorous debate and overcrowded with lobbyists and congressional aides, are dark and silent. A few congressional staff members gather for coffee in a senate basement café to discuss the latest pollings in Iowa and New Hampshire; but no work is being done to advance health policy. Prescription drug pricing reform, forging a deal on “surprise medical bills,” and a laundry list of other priorities will wait for another day.

Coronavirus Outbreak Raises Public Health Concerns

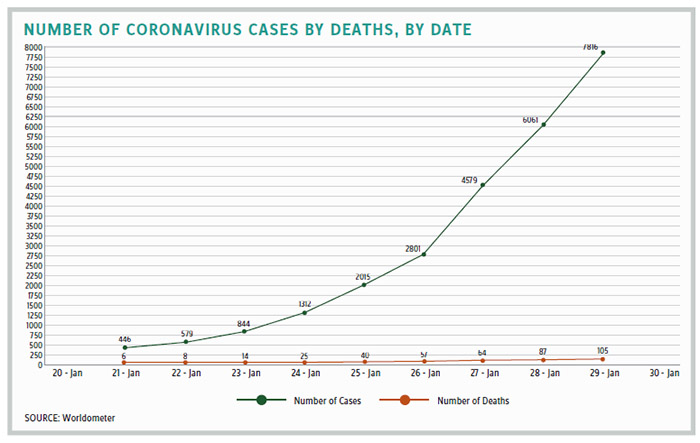

Halfway around the world, the streets of Wuhan, China (population 11.8 million), remain vacant as the alarming spread of a highly contagious virus has struck fear into the population. In late January, the “pneumonia” revealed itself as a novel coronavirus from the same family that caused the SARS epidemic that lasted from 2002 to 2004. By January 29, 7,816 had been confirmed as infected, up 1,228 percent from a week before, and 105 have died. (Editor’s note: Unfortunately, these statistics will be much higher once this issue is published.)

In response, China has effectively shut down Wuhan and the surrounding areas, placing them under quarantine with no air or rail travel. Yet, despite the quarantine, the virus has spread to 14 countries and territories outside China, with five cases announced so far in the United States.

How does a country quarantine almost 12 million people, anyhow? What do people do after a couple weeks of going through their savings when they cannot go to work? Does shutting down rail and air transportation block people from slipping out of the city to get food or get away from the dreaded virus (likely being unknown carriers themselves)? Or relatives from slipping in to assist their quarantined families, then returning to their own communities?

As the Zero Hedge blog points out, “The only way to end a contagion is to identify every carrier of the disease and immediately isolate them in full hazmat mode, and then track down every individual they had contact with during the incubation/asymptomatic period of the disease — up to two weeks — and isolate all of these individuals until they either develop the disease or pass through the crisis unharmed.”

This is the procedure used to stamp out the SARS virus in 2003, which killed nearly 800 people. But that crisis was much better contained than this latest public health threat that sent the stock market diving.

Here, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has taken the lead role in diagnosing and responding to the public health threat posed by the coronavirus on American soil. The CDC has placed over 100 Americans “under investigation” for the virus in 26 states — all individuals that recently visited China. Based on these patients’ travel histories and symptoms, the attending healthcare professional sends the CDC clinical specimens for testing and diagnosis. In addition, the agency has issued a Level 3: Avoid Nonessential Travel to China travel alert. Public health entry screenings also have been set up at 20 U.S. airports.

What Will Congress Do?

But even with Nancy Messonnier, the director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, claiming that the current overall health risk posed to the United States by coronavirus is “low,” talk has already materialized of a possible congressional response to the growing global health epidemic.

Such a response is not without precedent. Congress has previously passed funding measures to fight the rapid spread of global disease, with recent examples including resources to fight the Ebola virus threat that peaked between 2013 and 2016, as well as the outbreak of the Zika virus in 2015 and 2016. Still, even with an often-bipartisan sense of urgency in the form of public health crises, politics has gotten in the way.

In the case of the Zika funding package, it took Congress eight months to pass legislation after a request to do so from the White House. Republicans and Democrats fought over where to draw money for the response and whether the bill should limit how these resources got spent. Specifically, Republicans wanted funds kept away from Planned Parenthood clinics, while Democrats wanted a package without this restriction.

Let’s hope Congress does not engage in such tomfoolery again, when lives literally depend on the outcome. Wrap up the impeachment trial and get back to the people’s business!

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.