Medicare Advantage: The Solution To Value-Based Care

By John McManus, The McManus Group

As Congress grapples with complex ways to provide greater care coordination for seniors with multiple chronic conditions and value-based reimbursement schemes for prescription drugs, an obvious solution is being fundamentally ignored: greater enrollment in Medicare Advantage (MA).

As Congress grapples with complex ways to provide greater care coordination for seniors with multiple chronic conditions and value-based reimbursement schemes for prescription drugs, an obvious solution is being fundamentally ignored: greater enrollment in Medicare Advantage (MA).

MA plans offer comprehensive coverage of all medical goods and services at a capitated rate. They include all types of health plans: private insurance, HMO, and preferred provider organizations. These plans have every incentive to keep their enrolled patients healthy. They are experimenting with innovative risk-sharing arrangements with providers, from upside-only bonus contracts to fully delegated risk and capitation.

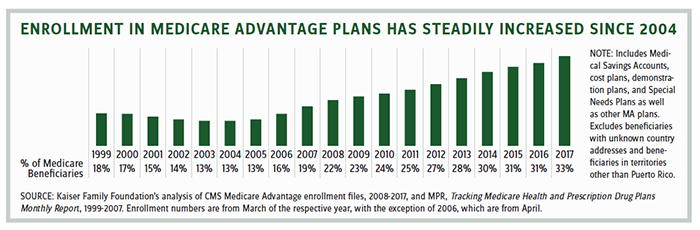

Enrollment in MA has steadily increased from 5.3 million beneficiaries in 2005 (comprising 13 percent of the population) to 19 million in 2017 (comprising 33 percent of the population).

Much of this growth is from the younger cohort of beneficiaries. Forty-eight percent of new MA beneficiaries are newly eligible for the program, and 10,000 people every day are eligible to enroll in Medicare. Only 2 percent of beneficiaries disenroll and revert to traditional Medicare once they join a plan.

A recent peer-reviewed study found that, on average, MA provides “substantially higher quality care” by outperforming Medicare PFFS (private fee for service) in 16 out of 16 clinical quality measures. Another study found that value-based care in MA has resulted in lower costs while improving survival rates.

A Total Flop

Meanwhile, Medicare’s attempt at value-based care in traditional fee-for-service has been a total flop. Obamacare established accountable care organizations (ACOs) — mostly hospital-led provider organizations to coordinate care — that share in the financial rewards or penalties based on their ability to hit cost and quality benchmarks. Over 10 million beneficiaries are now enrolled in an ACO. Yet rather than save the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) a projected $4.9 billion over a decade, ACOs have cost Medicare $384 million!

Only one in five of the 561 ACOs has any downside risk, and the Trump administration is developing a regulation to require greater risk-sharing by ACOs.

Joe Grogan, a senior health advisor in the White House, said, “ACOs need to accept risk sooner rather than later, provided that the metrics and benchmarks are transparent and simple and that those metrics hold ACOs accountable.”

Other value-based reimbursement schemes in traditional Medicare also are failing. In 2015, Congress established the Physician-Focused Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) to review and recommend alternative payment models (APMs). Of the 25 APMs PTAC reviewed, four were recommended for implementation and six for pilot-scale testing. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has not implemented any of them. A few weeks ago PTAC cancelled its June meeting, because “There are no proposals ready for the Committee’s deliberation and voting.” We are in gridlock!

A key obstacle to care coordination by physicians in traditional Medicare is the antiquated Stark self-referral law, which prohibits remuneration based on “volume or value.” The law was written nearly 30 years ago when policymakers were concerned with potential physicians self-dealing in a fee-for-service system.

But if physicians’ practices are prohibited from incentivizing their doctors to abide by treatment pathways, how can they deliver value-based care? It seems axiomatic that value-based care must permit remuneration based on value! More than 25 diverse physicians’ organizations from the full house of medicine have endorsed bipartisan legislation in both chambers that would resolve this problem in APMs. Congress needs to act!

“I Challenge Anyone To Understand This”

Implementation of the Merit-Based Incentive Program System (MIPS), meant to measure and promote physician quality improvements and resource conservation in fee-for-service, has been similarly unsuccessful. More than 60 percent of clinicians are excluded from the program for various reasons, and the rewards and penalties were so watered down for the rest that nearly three-quarters of physicians qualified as “exceptional performers.”

If nearly all are deemed exceptional, no one is exceptional! Everyone gets an A is no way to run a competitive program. Conscientious practices are wondering why they invested tremendous resources to get ready for the new program when there is no payoff.

Grogan expressed frustration that Health and Human Services work on value-based care is too complicated, pointing to ACOs and merit-based incentive programs. “I challenge anyone to understand this … . Not only would I not want my doctor to be thinking of this, but also I wouldn’t want my doctor to understand it at all.” He went on to criticize CMMI’s “underwhelming” performance and voiced support for the administration’s request to claw back $800 million from CMMI’s annual $1 billion budget.

The administration is now mulling several reforms to payments of physician-administered Part B drugs, including moving certain classes of drugs (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) from Part B to Part D, relaunching a reformed “Competitive Acquisition Program,” and experimenting with various value-based purchasing arrangements. All of these reforms are extremely complicated and could have substantial implementation challenges and unforeseen distortions of their own.

Is There A Better Solution?

A more productive approach to monkeying with payment schemes in fee-for-service is to simply enroll beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions in the capitated MA program and let those plans figure out the best way to provide healthcare to those beneficiaries. Nearly one-third of beneficiaries have two or more chronic conditions, such as vascular disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and COPD, and would certainly benefit from care coordination and disease management.

Upon Medicare eligibility, beneficiaries with two or more chronic conditions could be automatically enrolled in an MA plan that has expertise in treating those conditions. An opt-out could be provided to beneficiaries, but the presumption should be that those who have multiple chronic conditions should be enrolled in plans that can care for them best. Payments would be risk-adjusted so plans would have incentives and resources to serve those patients.

Similarly, dually eligible Medicare/Medicaid beneficiaries are currently randomly assigned to stand-alone prescription drug plans. These beneficiaries, who often have the highest drug utilization, should be assigned to high quality, integrated MA plans. A huge upside for the pharmaceutical industry is that MA plans have responsibility for total medical spend and are not fixated merely on the pharmaceutical component, which often leads to misguided and short-sighted formulary management decisions with no view to overall patient spend for all medical costs.

As MA has grown in popularity, particularly in urban and suburban communities, Democratic members who represent those areas have grown more comfortable with this important vehicle for private delivery. Republicans, who have historically been the proponents of MA, should seize the opportunity to expand the program before single-payer advocates can take the reins of power.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.