New Medicare Data And Litigation Provide Fresh Reasons For Congress To Reform 340B

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

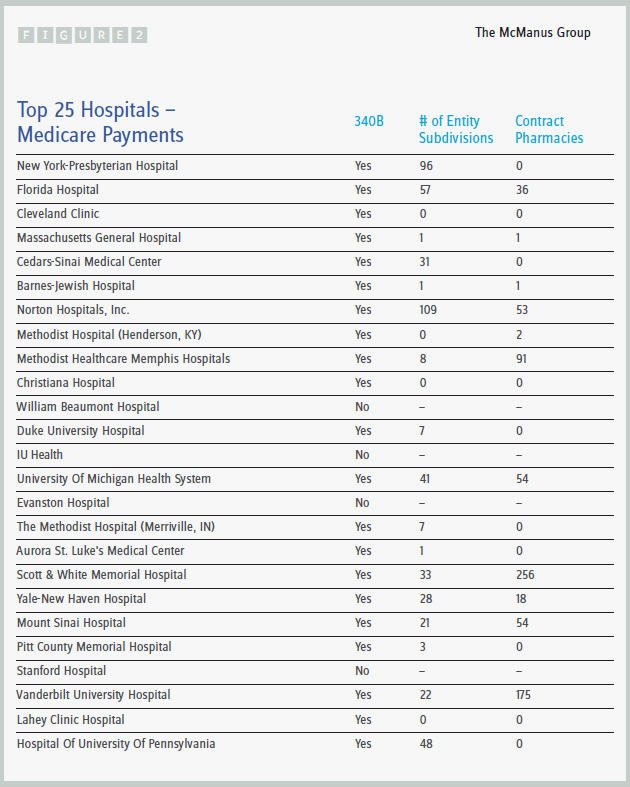

Medicare continues to release unfiltered information on provider utilization, which gives some illuminating information, particularly when that data is cross-walked to other sources. A case in point is the publication of the top Medicare hospital billers in the country: 21 of the top 25 are 340B hospitals and therefore access the substantial pharmaceutical discounts under that program. (See Figure 2.)

Medicare continues to release unfiltered information on provider utilization, which gives some illuminating information, particularly when that data is cross-walked to other sources. A case in point is the publication of the top Medicare hospital billers in the country: 21 of the top 25 are 340B hospitals and therefore access the substantial pharmaceutical discounts under that program. (See Figure 2.)

All of the top 10 hospitals are 340B hospitals, and many have far-flung subdivisions and contract pharmacies that enjoy access to the program. New York-Presbyterian Hospital, the number one Medicare biller, has 96 subdivisions; Cedars-Sinai Medical Hospital has 31 subdivisions; and Norton Hospitals in Kentucky has 109 subdivisions and 53 contract pharmacies.

Under the statute, these hospitals are entitled to discounts ranging from 23 percent of the average manufacturer’s price to 50 percent and often more for every outpatient drug provided to every patient, regardless of whether they have insurance or Medicare coverage. Nothing requires 340B hospitals to pass these discounts on to the patients — they are simply a vast revenue source, and most of these hospitals continue to charge market rates to Medicare, commercially insured patients, and even the uninsured.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the 340B program in several important ways:

- It increased the size of the minimum discount from 15 percent to 23 percent because it is tied to the identical higher Medicaid rebate that PhRMA negotiated with then-Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus.

- It increased the number of hospitals eligible for the program by substantially expanding the Medicaid program, a key component in the formula for determining 340B eligibility.

- It explicitly increased the number of 340B hospitals by designating certain rural hospitals and other entities as eligible.

Just as important as these statutory expansions is the growing trend of hospital acquisition of physician practices, which studies now show to have substantial distortionary effects on the market. A June study published by the Berkeley Research Group found that at least 120 340B hospitals had acquired physician-based oncology practices between 2008 and 2012, which resulted in a shift of 11.6 percent of the overall chemotherapy claims volume from physician offices to hospital outpatient departments. For 86 of the hospitals, the acquisition led to a 20 percent or greater increase in the volume of chemotherapy claims billed to Medicare.

How can free-standing, physician-led practices compete with 340B-eligible hospital-based systems that are acquiring oncology practices at such a rapid rate when a major cost component is the acquisition of chemotherapy drugs? The Berkeley study notes that, “By acquiring physician-based oncology practices, 340B hospitals are able to increase volume of oncology claims that use chemotherapy drugs and thereby increase the margins realized on the reimbursement of those drugs.” In Figure 1 (below) is an example of this pricing differential.

The public policy concern is that Medicare and commercial insurers pay substantially more for care delivered at hospitals than care delivered in physician offices. Berkeley estimates this cost Medicare and Medicaid nearly $200 million from 2008 to 2012.

There was some hope that the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) would finally release a mega-regulation clarifying certain aspects of the 340B program and possibly address the more abusive aspects of the program that have emerged over the last several years. In the 22 years of the program, almost all policy was executed through sub-regulatory guidance and outside the normal transparent rulemaking process. For example, the policy change to allow 340B hospitals to contract with multiple pharmacies was executed through “sub-regulatory guidance” — that is, outside the transparent notice and comment rulemaking process. HRSA announced earlier this year that it would issue a regulation addressing the following areas:

- definition of the patient

![]()

- compliance requirements for contract pharmacy arrangements

- hospital eligibility criteria

- eligibility of off-site facilities.

But litigation by PhRMA over the definition of “orphan drug” stopped that regulation in its tracks. PhRMA asserted that HRSA violated the Administrative Procedure Act because HRSA did not have the authority to issue the final rule, and even if it did have that authority, the statute exempts all uses of orphan drugs from 340B, not just the orphan indication.

The District Court ruled in favor of PhRMA on HRSA’s legislative authority to issue the regulation, stating that HRSA only had authority in three narrow areas:

- the establishment of an administrative dispute resolution process

- the methodology for calculating the 340B ceiling price

- the imposition of civil monetary sanctions.

Notwithstanding that District Court decision, HRSA updated its Web page on June 18, 2014, and asserted that the decision did not, in fact, invalidate the agency’s interpretation that manufacturers must continue to provide 340B discounts for non-orphan conditions of orphan drugs.

This raises a fundamental question: How can HRSA continue to implement a policy that was created through a process the District Court has found to be invalid?

This may be the worst of all possible outcomes for the pharmaceutical industry: The District Court’s decision hamstrings HRSA from reining in egregious aspects of the 340B program but does not prevent it from continuing to demand 340B discounts for non-orphan indications for orphan drugs.

Unless and until HRSA appeals the District Court decision on its fundamental ability to issue regulations, the pharmaceutical industry and provider community is left in limbo and will continue to operate under the current regime.

In the 22-year history of the 340B program, Congress has held exactly one oversight hearing. Perhaps this is because 340B hospitals and other qualified 340B recipients reside in every Congressional district, while pharmaceutical companies are limited to a few zip codes in several states. But real reform of the 340B program must now come from Congress.

The easiest thing for Congress to do would be to punt on substantive matters of the 340B expansion and simply empower HRSA to issue a rule that would clarify and implement all aspects of the program.

But that would be a lost opportunity to fundamentally reform a program that has spiraled out of control and bears little resemblance to its original purpose of providing discounted outpatient drugs to uninsured and indigent hospital patients.