Restructuring Of Medicare Part D Imminent

By John McManus, The McManus Group

The fundamental framework of Medicare Part D, enacted nearly 16 years ago,

remains sound:

- delivery through competing private plans, rather than a single, government-controlled structure dictating prices and formulary coverage and placement

- catastrophic protection for patients with high costs (unlike the rest of Medicare)

- extra assistance for low-income beneficiaries directly through Medicare rather than disparate state Medicaid programs.

The benefit has been a success: It costs 45 percent below initial estimates, offers improved health through better prescription drug adherence, and is popular with over 90 percent of seniors who now have comprehensive coverage. Studies have shown that this improved coverage has led to an 8 percent decrease in hospital admissions and even a more substantial decline for conditions such as congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Seniors’ longevity has increased as deaths in treatable diseases have declined.

The benefit has been a success: It costs 45 percent below initial estimates, offers improved health through better prescription drug adherence, and is popular with over 90 percent of seniors who now have comprehensive coverage. Studies have shown that this improved coverage has led to an 8 percent decrease in hospital admissions and even a more substantial decline for conditions such as congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Seniors’ longevity has increased as deaths in treatable diseases have declined.

Yet, new challenges have emerged, which require a fundamental reexamination and modernization of the program.

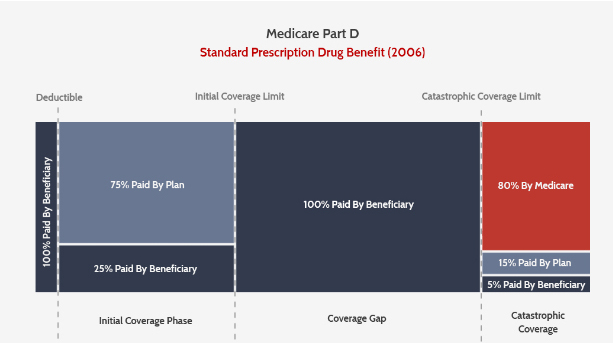

When Congress was constructing the benefit in 2003, then-CMS Administrator Tom Scully notoriously observed that a stand-alone prescription drug plan “does not exist in nature.” The architects of the benefit were extremely worried that the competing prescription drug plans critical to the pluralistic delivery of the benefit may not participate if they felt the risk was too high. Therefore, they required Medicare to cover 80 percent of the costs, once a beneficiary reached the catastrophic phase of the benefit.

Though a paucity of plans has plagued the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) health exchanges, that has not been a problem in Part D. This year, there are 782 prescription drug plans and over 2,000 comprehensive Medicare Advantage plans with numerous choices in every region of the country.

After more than a decade of operation, it is time to remove the “training wheels.” Plans can and should accept more risk, and therefore have more skin in the game in controlling drug costs. Plans are only on the hook for 15 percent of costs in the catastrophic, with the remaining 5 percent left with the beneficiary.

REDUCE REINSURANCE AND ELIMINATE COPAY IN CATASTROPHIC PHASE

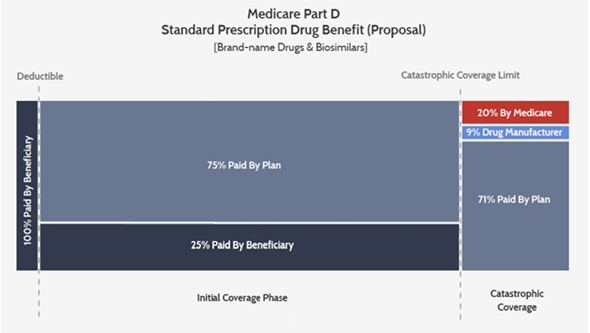

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has suggested decreasing Medicare’s 80 percent “reinsurance” in the catastrophic benefit to 20 percent. That proposal has been endorsed by the Trump administration in successive budgets. A couple weeks ago, the bipartisan House Ways & Means and Energy & Commerce Committees released a draft bill inviting comment on plans to phase in such a change over four years.

In addition, there is growing bipartisan consensus that beneficiary exposure on prescription drug costs must be capped, whereby the current 5 percent copay in catastrophic would be eliminated entirely. Many policy makers and manufacturers alike have noticed abandonment and nonadherence because a 5 percent copay can still be substantial on expensive drugs. (That copay was a political compromise between the House-passed zero beneficiary liability and Senate 10 percent.) The house bipartisan draft bill would eliminate the copay.

ADDRESSING EMERGING DISTORTIONS

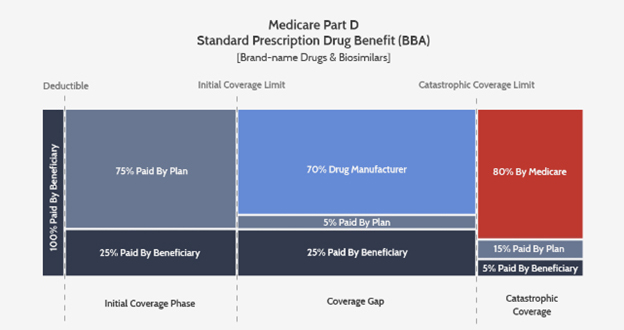

In 2010, the ACA made changes to the benefit to address a perceived weakness mercilessly hammered by Democrats when the Republican Congress enacted Part D: the “donut hole” or coverage gap between the initial benefit where the plan covered 75 percent of costs and the point the catastrophic benefit kicked in. That change required a 50 percent price control on brand-name products in the coverage gap and gradually phased in plan coverage to 25 percent.

The ACA also temporarily restrained the growth of the catastrophic threshold for 10 years — i.e., until 2020, when the old formula kicks back in and the threshold is projected to jump by 30 percent, from $5,100 in 2019 to $6,650 in 2020. This is known as the “catastrophic cliff” and is a key reason congressional action is likely this year to prevent it from taking effect.

Last year, Congress created more distortions to the benefit when it enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 by increasing manufacturer liability to 70 percent and absolving plans for all but 5 percent of risk in the coverage gap. Importantly, those manufacturer contributions count toward the catastrophic benefit, meaning more beneficiaries reach catastrophic, and do so sooner.

High-cost enrollees — those hitting the catastrophic benefit — have seen costs rise at over 10 percent annually, while other enrollees’ costs have actually declined. The result: Reinsurance accounts for more than two-thirds of the costs of Part D today, up from just one-third in its first year of operation.

Further exacerbating these emerging distortions is that negotiations among manufacturers and PBMs and plans have evolved in ways not foreseen by policymakers in 2003. There was an expectation at that time that plans would negotiate a combination of discounts and retrospective rebates. Now all negotiations are focused exclusively on rebates, resulting in inflated list prices and copays to beneficiaries with high costs. Plans use those resources to restrain premiums in order to attract lower-cost enrollees.

The Trump administration issued a proposed rule earlier this year prohibiting those rebates as violating the Anti-Kickback statute. But a final rule is held up, in part, because the Congressional Budget Office has projected it to cost Medicare $177 billion over 10 years, on the theory that 15 percent of those rebates will not be passed on in lower prices. That score makes it likely that the rule will not be finalized or will be blocked by Congress and used to finance other priorities. (CBO’s substantial misestimates of pharmaceutical policy are, unfortunately, not relevant.)

AMERICAN ACTION FORUM PLAN

The American Action Forum (AAF), a center-right think tank, has suggested a reform that would shift the manufacturer liability from the discrete period in the “coverage gap” to an open-ended 9 percent of costs above the catastrophic threshold. That may leave beneficiaries in the coverage gap for a longer period of time, but AAF suggests lowering the catastrophic threshold in order to keep beneficiaries whole (i.e., not make the beneficiaries pay more) or allow them to experience slight savings.

AAF also suggests giving plans more tools such as step therapy and prior authorization to lower prescription drug costs, particularly for protected classes of drugs. But last month, CMS pulled back from its proposal earlier in the year to allow step therapy for patients with HIV/AIDS. In the final Part D rule, CMS limited step therapy to only new starts (enrollees initiating therapy) for five of the six classes and excluded antiretrovirals entirely, a key win for AIDS advocavy groups.

CMS also backed off its earlier proposal to limit price increases for drugs in the six protected classes to the consumer price index. But the rule did finalize the policy to allow step therapy for Part B drugs in Medicare Advantage.

This summer, we are likely to see the committees advance a restructuring of Part D. What remains unclear is whether Speaker Pelosi’s interest in requiring “arbitration” — a clever repackaging of “Government Negotiation,” a key tenet of the left’s desire to control drug prices — will make it into a legislative package.

The wildcard remains President Trump, who has said he has no “red lines” in the prescription drug debate, but remains besieged by Democrats with calls for impeachment. He sees a success on prescription drugs as being critical to winning the senior vote in 2020.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University.