Leading Business With Science: Geert Cauwenbergh of RXi

By Wayne Koberstein, Executive Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @WayneKoberstein

Industry Explorers Blaze On: A series of stories of longtime leaders, still active in the industry, sharing their historical perspectives on life sciences industry innovation.

Life roads seldom travel in a straight line. Many if not most of the explorers in this industry have started their careers in one direction before taking another route entirely. Geert Cauwenbergh now can look back at his almost four decades in the industry — from his formative years working with Paul Janssen building a small company into a global phenomenon, to his later years as a startup entrepreneur with RXi — and reflect on how most of it has turned upon a snap decision. It was the early 1970s, and he was a young college entrant in his native Belgium.

“When I was done with my high school, I told my mom that I wanted to register for medicine,” he recalls. “I went to the University of Leuven, and I asked the people at the registration desk how many people have registered so far for the first year of medicine? They said there were about 1,200, and I said, ‘What? I don’t want to be part of such a big pack. Is there anything in science that is close to medicine where there are not so many people?’ And they said, ‘You could major in biology, that’s close to medicine.’ I came back home and my mom asked, ‘So, you registered for medicine?’ No, biology!”

Explaining Science

Cauwenbergh eventually earned his master’s degree in an even less-populated field, especially in a near-landlocked country like Belgium — marine microbiology — thus satisfying both his love of science and preference for traveling in smaller packs. He found the first opportunity to apply his education in an unexpected, though not unlikely place: chocolate.

“A Belgian chocolate factory wanted to get started with microbiology quality control. They realized my education in marine microbiology had nothing to do with food microbiology, but they hired me anyway. And after a year, I had built the first microbiology quality- control lab in the food industry in Belgium.”

Impressive as it was for its time, Cauwenbergh’s QC lab was just a preamble to his first job in pharmaceuticals. In 1979, after a German company acquired the chocolate factory and centralized all operations, he was left with the menial job of taking samples for a lab in Germany. He eagerly sought other options and soon joined the proto-global Janssen Pharmaceutica in Beerse, Belgium, taking an open sales position.

Little Janssen, forever dedicated to discovering and developing new therapeutic molecules, was then extending its presence and making itself known worldwide. Operations were expanding rapidly, new products were entering the market at an unheard-of rate, and the company used its in-house talent as it did everything else — creatively. When Cauwenbergh’s sales rose above his peers, the head of marketing recruited him to head promotional efforts for the company’s antifungals, serving in its Belgium and Luxembourg offices. Marketing for Janssen then mainly consisted of explaining and presenting evidence that its new drugs made treatment of some conditions possible for the first time.

Cauwenbergh took to the work instinctively, gleaning the key attributes of a drug and often showing them visually in the clinical data charts. A trip back to Beerse, however, led to a fateful encounter. It was a chance meeting that illustrated how, despite its acquisition by Johnson & Johnson in 1961, the Janssen company still operated quite independently under its founder, “Dr. Paul” Janssen.

“I bumped into Dr. Paul in the elevator, and he said, ‘Hi, Geert, how is miconazole marketing doing?’ We had never spoken before, but he knew my name and he knew what I did.” Janssen invited Cauwenbergh into his office and told him he was working in the wrong department, given his background and skills. “I’ve heard you give some talks, and the people in research like you,” said Janssen. “You should go to research.”

Despite having a great time in marketing, Cauwenbergh answered his boss’s call and went to work in Janssen’s R&D arm. He dove into the assignment and, in only nine months, led the development and won FDA approval of a new, rare-disease indication for the company’s second-generation antifungal, ketoconazole (Nizoral). Yet just as his R&D role seemed assured, the lead marketer for Nizoral left the company, and Cauwenbergh was the obvious candidate to fill the empty position. “The head of marketing called me and said, ‘You’re the only one who knows the product, and you know marketing. Come back.’” His mission: make Nizoral a global product.

INTERNATIONAL MEETING ON THE WOUND HEALING EFFECTS OF KETANSERIN

Beerse, Belgium

November 2, 1987

Highlighted in front row: “Dr. Paul” Janssen (left), Geert Cauwenbergh (right)

Taking It Global

Under Cauwenbergh’s leadership, Nizoral grew to become a global market leader. It stayed on WHO’s essential drug list from 1984 to 1997, when Janssen and others launched a new generation of better antifungals to replace it. Drawing from company scientists who returned to Belgium from the former African colony, Zaire, Janssen had actually created the antifungal market with miconazole, and other companies were playing catch-up. Janssen researchers’ original quest to cure a third-world disease had achieved global success as the fungal-fighting agents took on multiple human, animal, and even agricultural uses. When the company turned its attention to the next wave of new antifungal compounds in its pipeline, Janssen called Cauwenbergh into his office again.

“Remember I said, you belong in R&D,” Janssen told him. “That’s okay, but I’m having a ball in international marketing,” Cauwenbergh replied. Janssen was firm: “No, no, no, I want you in R&D.” He had decided to make Cauwenbergh the head of development for the company’s emerging dermatology line — which, of course, consisted mostly of antifungals at the time — as well as infectious diseases, a new area for the company.

Janssen’s reason for wanting Cauwenbergh in R&D was straightforward: “He felt I was very good at communicating complex scientific messages to the general public, and to nonscientists in the industry. I would say that skill belongs in marketing, but marketing for him was only window dressing; he believed a good product would sell itself on the strength of scientific evidence. Actually, in 1986, he basically abolished international marketing for a while.”

To the extent that well-explained science can persuade people — from early stakeholders to gatekeepers down the line — Janssen may have been correct, Cauwenbergh believes: “When you can visualize what something does in clinical form, it hits home.” The ability to understand and explain the science of a product begins in development, he adds. “Keep an open mind. Look at early observations in clinical trials. You can learn a lot from them, especially when you have a new compound in a new class.”

Credentialing Up

Despite Janssen’s insistence, Cauwenbergh’s move back to R&D was hardly simple or easy. He knew heading the development group for an entire therapeutic area could exhaust the goodwill he had earned previously with researchers who outranked him in education and experience.

“At that point, I still only had my master’s degree in microbiology, and I told Dr. Paul I didn’t belong in research. How would the others feel about me running a whole medical clinical department? He saw my point, and we concluded I would need to earn a doctoral degree. He picked up the phone and called the dean of the faculty of medicine at the University of Leuven, my alma mater, and told the dean I would like to do a residency in dermatology.”

Learning Cauwenbergh had no medical degree, the dean offered to send Cauwenbergh a list of medical books to read, in preparation for a jury exam to qualify for the residency program. But, as part of the deal with Janssen, while in the residency he would continue working for Janssen on the development of Sporanox (itraconazole), a compound he had just selected from the company’s stable of antifungal candidates.

It turned out to be a good selection. Not only did Sporanox eventually see use widely against toenail and fingernail fungus, it was the first oral agent approved for fungal infections in immuno-compromised patients, such as blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and aspergillosis — affecting thousands of HIV-infected, bone-marrow transplant, and cancer patients.

As the development of Sporanox and other products under his responsibility progressed, Cauwenbergh worked on his doctoral thesis and saw patients once a week supervised by a physician. Five years later, he had earned a Ph.D. in medical sciences degree and would continue leading the dermatology and infectious diseases groups in R&D until Dr. Janssen’s retirement from the company in 1994. During the same period, Cauwenbergh initially took on responsibility for the company’s first anti-HIV drugs, the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, which then had problems with drug resistance and uncertainty over their half-life in vivo, based on animal studies. With the latter, Cauwenbergh literally took the problem into his own hands — testing the drug on himself.

“In those days, I was allowed to inject myself to determine what animal species would be closest to humans in how it metabolized the drug. When I was in charge of the department, I made it a point of honor that I would not test a drug in patients before I used it on myself, and I kept that promise. I’m not allowed by the current rules to do it, otherwise I would. In this case, we found I was very close to a pig, which helped us choose to do the PK studies in pigs instead of rats and dogs.”

Once the half-life problem had a solution, Janssen’s non-nucleosides continued on the development path. Two of them, Edurant (rilpivirine) and Intelence (etravirine), made it to market and are still used in anti-HIV “cocktail” therapy. Early in the game, however, a new figure entered the scene to continue the company’s pioneering achievements in anti-HIV therapy. In 1994, Janssen’s other “Dr. Paul,” Paul Stoffels, returned to Beerse from Rwanda and subsequently took charge of the company’s HIV-drug development.

From left to right: Dr. Paul Stoffels (then head of infectious diseases, Janssen), Dr. Piet De Doncker (Cauwenbergh’s right hand in clinical trial management), Geert Cauwenbergh

But that story begins years earlier, in 1989, when Cauwenbergh was still running dermatology and infectious diseases, and he hired the young, idealistic Stoffels for work in Zaire. Having begun his education in Africa, where he helped treat and study AIDS, Stoffels had just contracted with an NGO (nongovernmental organization) to run a clinic there. “I don’t want to work for the pharmaceutical industry,” he declared, thus winning Cauwenbergh’s admiration for his candor. “But the clinic job does not pay well, and I have three kids and a wife. I’m willing to help you out with supervising and coordinating your AIDS-related clinical trials there. We do a lot of work in cryptococcal meningitis in AIDS patients.”

After about a year and a half overseeing trials for Janssen, Stoffels took on responsibility directing all of the company’s activities in Zaire. But in short order, those duties evaporated as local violence mounted. What happened next is better narrated in Cauwenbergh’s words:

“Paul didn’t want to leave Africa. He’s in love with Africa. He took his family to Rwanda, and they traveled on my budget, flying to Goma, the Congolese city on the border with Rwanda, on an old DC8. Then he drove into Rwanda and set up shop close to the main hospital, the CHU of Kigali [Kigali University Hospital Center]. For more than a year and a half, I sent him all the latest publications, and he managed a lot of our trials from the hospital. I visited once, and one half of the pharmacy held all clinical trial products in development, and the rest was full of products from all the other drug companies selling there.”

When genocidal violence between the Tutsi and Hutu tribes erupted in Rwanda, Stoffels sent his family back to Belgium but remained in Kigali at first, hoping to protect some Tutsi people who were taking care of his house there. Cauwenbergh forced the issue. “Finally, I was told by Janssen management to call him and tell him, ‘Paul, you take the next flight out or you have no job anymore.’ So he took the next flight out, luckily — that was actually the last flight possible.”

Setting The Next Stage

At the outcome of this dramatic interlude, Cauwenbergh’s world was in for another big change. Stoffels had returned to become the natural candidate to take over leadership of the infectious diseases development group, most immediately focused on HIV, based on his extensive study of the disease in Africa. With dermatology well in hand, Cauwenbergh suddenly felt at loose ends.

“I was sitting there, supervising two really capable individuals, so I looked for something else to do,” he says. “I was focusing more on early clinical trials because I like the observational adjustments you can do at that stage, switching the drug to different tracks as a result of clinical observations.”

His first development candidate, ketoconazole, illustrates his point. When testing the drug in high doses to treat cryptococcal meningitis, he noticed male patients reported a loss of libido. He then decided to measure patients’ hormones, and the results showed extremely low, down to “castration levels” of testosterone in those patients. Ketoconazole was causing abnormally low testosterone, which explained the loss of libido. A light went on.

“How about prostate cancer?” — that was the question he asked in the face of the clinical observation. He pushed the idea of developing a separate indication for the drug in prostate cancer, where testosterone-reduction had been an effective strategy. The program gained management approval, and the ultimately successful development program secured indications for ketoconazole in prostate cancer. It is still in use as second- line therapy for advanced disease.

For Penny, For Pound

After Paul Janssen had “retired,” only to become cofounder and head of the new Center for Molecular Design, and Stoffels headed off as well — to run the HIVdrug spinoff Tibotec — Cauwenbergh found himself dealing more and more with the corporate bureaucracy, and enjoying it less. “It was becoming too big, with lots of committee meetings I had to attend, and nobody would make a decision,” he says. “I would push an idea, and some political person would make sure that the decision got killed. I was fed up.”

Time for another fateful encounter. In 1994, Cauwenbergh crossed paths with Ron Gelbman, then J&J’s pharmaceutical group chairman, who had always been friendly. “Ron asked me how things were going, and I said ‘I’m going to change jobs. I’m going to work with another company.’ But he said, ‘Come to the United States. We’re going to consolidate all J&J dermatology products and companies, prescription and consumer, into one, and we need somebody to lead the R&D group.’” So, instead of fleeing the corporate environment, Cauwenbergh jumped into the center of the maelstrom. He soon moved from the quiet rural setting of Beerse to the New York area, where he would go to work in J&J’s New Jersey headquarters in New Brunswick.

“Consolidation didn’t sound then the way it sounds these days. Now it means you’re spending too much money and you need to cut costs. In those days, I didn’t get it yet, I was a pure research guy. I moved over to the States, and I had a ball.”

Cauwenbergh did enjoy his time in the job, during which he and his family became true natives of the great metropolis around New York City, as well as “pharma row” in New Jersey. But after giving it the better part of a decade, he had concluded J&J Dermatology was coming to a creative dead end. In his view, the company was constraining the prescription side of its R&D efforts in dermatology in favor of its true comfort zone — retail.

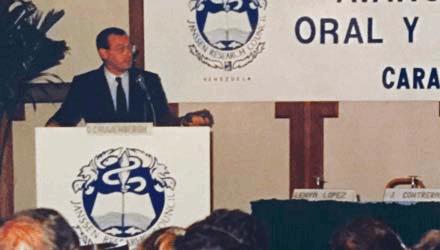

Geert Cauwenbergh speaking in Venezuela to a group of physicians about opportunistic infections in AIDS patients.

“It became clear consolidation was not taking us anywhere,” he says. “J&J didn’t want to do further drug development. It is a big skin care company, but really only in consumer skin care, not the development of drugs. J&J’s Remicade is used in psoriasis, and it has some successor compounds available, but only intravenous drugs. The company still has no oral drugs in dermatology; that’s really not its space anymore.”

Once again, at just the right time, came the fateful crossing of paths: In 2001, Cauwenbergh encountered Robert Wilson, then J&J’s vice chairman. When Wilson asked how it was going, Cauwenbergh was characteristically frank: “Bob, I have the impression that I’m wasting your money and you are wasting my time,” he said. “We’re sitting on so much IP in dermatology that we’re not using, why not create spin-outs?” Wilson liked the idea. Yet, he advised Cauwenbergh to prepare for selling the concept to the incoming chairman, William Weldon. “One point you have to make — no commercial drugs, no revenue for the spinoff,” said Wilson. “It has to be an R&D company only; we don’t want to give revenue away.”

Weldon was evidently convinced, because Cauwenbergh spent his remaining years at J&J launching dermatology and other R&D spinoffs. Those included DermCo, based on J&J IP as a result of its collaboration with the University of Michigan; Transderm, a topical-delivery company; and others such as a haircare company and a company based on biodegradable catheter technology.

See part two in our May issue for the rest of Geert Cauwenbergh’s story, when he leaves Big Pharma to go out on his own, into the startup world of biopharma.