Pfizer's Response To Counterfeit Drugs

By Camille Mojica Rey, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter

This is the second article in a five-part Life Science Leader series examining the current state of the counterfeit medicines problem. A previous story looked at efforts to quantify the crime. Upcoming stories will look at what is being done by one international coalition to fight the crime, describe efforts to educate patients, and profile a company working to put unique identifiers on individual pills.

In May 2016, the FDA warned consumers that fake versions of Viagra and Lipitor were being sold in Mexican border towns. In September, Polish police shutdown what was reportedly the largest laboratory in the world making phony versions of erectile dysfunction (ED) drugs. Authorities seized 100,000 pills for ED, including counterfeit Viagra.

These fake drugs are easy money for criminals worldwide, says the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, a New York-based research group partially funded by the pharmaceutical industry. The group estimates that counterfeit drugs will generate $95 billion this year, an increase of 26 percent since 2010.

“It’s a huge and complex problem that continues to evolve and grow,” says John Clark, chief security officer for Pfizer, which makes Viagra and Lipitor, as well as many other popular medicines. Especially in the age of the internet, the growth in the counterfeit drug market is driven by the low-risk/high-reward nature of the crime, Clark says. “We have heard reports of links between those selling counterfeit medicines and terrorist groups,” he says.

In response to this mushrooming problem, Pfizer has created a global security team. Its members have a variety of backgrounds, from law enforcement to forensic chemistry. Working together, they initiate and develop cases with the goal of disrupting and dismantling major manufacturers and distributors of counterfeit Pfizer medicines. “Our efforts to combat the counterfeiting of medicines and our investment in addressing this problem are to ensure that patients who seek a Pfizer medicine obtain an authentic Pfizer medicine that is safe and effective,” Clark says.

THE POPULARITY OF PFIZER’S MEDICINES AMONG CRIMINALS

This is a real concern, given that the company estimates that, to date, there have been 90 counterfeit Pfizer medications seized in 111 countries. In 2011, Viagra accounted for 85 percent of seizures of Pfizer’s medicines and products worldwide. That number dropped in 2015 to 49 percent of Pfizer seizures as the company’s other drugs have grown in popularity. Lipitor, for example, is one of its drugs that is currently being widely counterfeited. Three years ago, Chinese authorities seized 3 million doses of the drug used to lower low-density lipoproteins, or LDL, the “bad” cholesterol. “Criminals are counting on Pfizer’s reputation to sell their counterfeit products. Their intent is to fool patients into thinking they are getting an authentic Pfizer medicine,” Clark says.

This is a real concern, given that the company estimates that, to date, there have been 90 counterfeit Pfizer medications seized in 111 countries. In 2011, Viagra accounted for 85 percent of seizures of Pfizer’s medicines and products worldwide. That number dropped in 2015 to 49 percent of Pfizer seizures as the company’s other drugs have grown in popularity. Lipitor, for example, is one of its drugs that is currently being widely counterfeited. Three years ago, Chinese authorities seized 3 million doses of the drug used to lower low-density lipoproteins, or LDL, the “bad” cholesterol. “Criminals are counting on Pfizer’s reputation to sell their counterfeit products. Their intent is to fool patients into thinking they are getting an authentic Pfizer medicine,” Clark says.

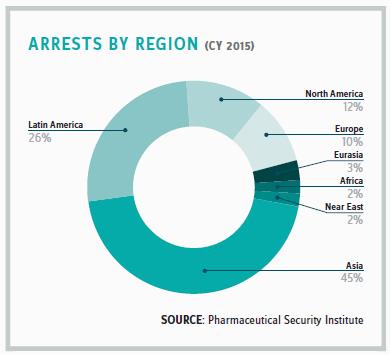

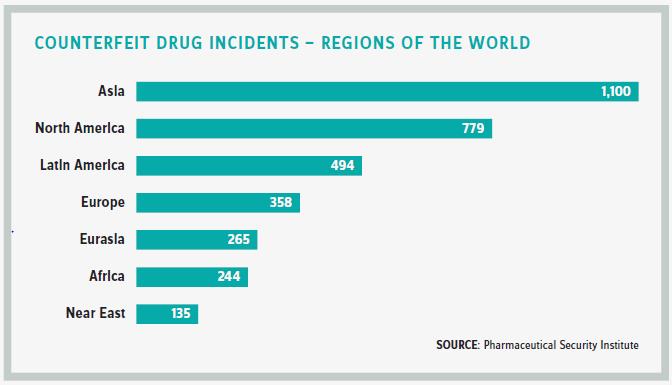

Most counterfeit drugs are made in China for export. In the last five years, however, there has been a shift to selling those drugs within the country. The 3 million doses of Lipitor seized in China three years ago were intended for sale to its growing middle class.

Clark called the recent discovery of the manufacture of counterfeits in the U.S. a worrisome development. The DEA recently shut down three separate operations making counterfeit Xanax in the San Francisco Bay Area, Texas, and Florida. Authorities found some of the fake Xanax contaminated with fentanyl, which caused a number of deaths in Florida.

![]() "Unique identifiers won’t be the silver bullet to stop counterfeiting, but when you get the rare instance of counterfeit medicines breaching the supply chain, this kind of track-and-trace will be phenomenally helpful."

"Unique identifiers won’t be the silver bullet to stop counterfeiting, but when you get the rare instance of counterfeit medicines breaching the supply chain, this kind of track-and-trace will be phenomenally helpful."

John Clark

Chief Security Officer, Pfizer

SECURING THE GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN

Protecting patients from counterfeits means securing global supply chains. To that end, the industry and government agencies are turning to unique identifiers or bar codes. In the U.S., Congress passed the 2013 Drug Supply Chain and Security Act. The law requires drug companies to work in cooperation with the FDA to “build an electronic, interoperable system to identify and trace certain prescription drugs as they are distributed in the United States.”

According to Clark, Pfizer is testing the use of unique identifiers on packaging. “We can check the pedigree of a medicine to see its last stop along the supply chain,” he says.

The law sets 2023 as the goal for the full implementation of this system in the U.S. But even today, a patient in this country who goes to a brick-and-mortar pharmacy has a very slim chance of getting a counterfeit medicine. “The supply chain here is incredibly secure,” Clark says. He recalls the last breach of a counterfeit Pfizer medicine in the U.S. supply chain occurring more than a decade ago. “When a rare breach occurs, our regulatory agencies ensure that these medicines are quickly pulled off shelves.”

The bigger problem for Pfizer and other large companies is that they operate in a global marketplace. Implementation of a global track-and-trace system is happening, though slowly. The legislation required on an international scale to implement a global track-and-trace system is an enormous undertaking, so it is only slowly coming together. There needs to be consensus on the system that will be used to track medicines and whether the tracking markers will be placed on pallets, packages, and/or individual doses. This isn’t just a pharmaceutical company issue but includes distributors, warehouses, pharmacists, and clinics. Each of the players has to invest in the same equipment so bar codes can be read, receipt of medicines can be verified, and forwarding can be documented.

Getting global agreement on how to use unique identifiers has been difficult, Clark says. Where even to place the identifier — on the package or on the pallet — is being debated. “There are a lot of hurdles, but we are maybe two years away from having it formally implemented industrywide,” he says. “Unique identifiers won’t be the silver bullet to stop counterfeiting, but when you get the rare instance of counterfeit medicines breaching the supply chain, this kind of track-and-trace will be phenomenally helpful.”

In addition to unique identifiers, Pfizer has been working on a variety of ways to track and trace their products. Clark’s team works closely with Pfizer’s manufacturing division to implement overt and covert capabilities on the packaging. “We have already instituted track-and-trace methods that allow us to know whether medicines from one market are being sold illegally in another market,” he says.

THE INTERNET PROBLEM

But it’s the ability of patients to buy supposedly authentic drugs online from rogue pharmacies that is the biggest risk to patient safety. “That’s when they really roll the dice,” Clark says.

In 2013, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) did an assessment of 10,000 online pharmacies. Its survey revealed that about 97 percent did not meet pharmacy standards. “We are tackling that problem as best we can and targeting illegitimate online pharmacies,” Clark says.

In fact, Pfizer is an industry leader in this area. The company partnered with Microsoft in 2012 to develop a computer algorithm that links what appear to be separate and distinct online pharmacies and identify the affiliate network behind them. “What we find is that there is really one organization running thousands of sites,” Clark says.

As of June, Pfizer’s security team has disrupted 21 affiliate networks consisting of 6,597 rogue online pharmacies. “We take a lot of pride in that fact,” Clark says. Like the IACC (International AntiCounterfeiting Coalition), Pfizer works with payment service providers like VISA to ensure these criminals cannot do business anymore. “We limit their banking options,” Clark says.

Pfizer’s programs have been so successful that, at a recent meeting of security officers, five companies expressed interest in partnering with them and expanding their efforts to take down illicit online pharmacies. “It behooves us all to work together,” Clark says. “We all need to be doing a better job of making it harder for this problem to grow.”

SLOW PROGRESS WORLDWIDE

The pharmaceutical industry as a whole is slowly making progress in the fight against pharmaceutical crime. It’s a difficult problem to combat when no one even knows the true extent of it. In any one country, people see only part of the problem. “There’s no one country or agency to pull it all together,” Clark says.

He points out that there is much more cooperation among law enforcement agencies around the world. Law enforcement officials in China, where most counterfeits are made, have been among the most collaborative. That’s because the Chinese authorities see the negative impact the fake drugs are having on their population. “They will always work on a case when given the evidence,” he says.

The work Pfizer and other companies do to train law enforcement around the world is helping both to raise awareness and detect crimes. Pfizer’s security team has trained law-enforcement agencies in 151 countries. What the team encounters around the world, however, are inconsistencies in legislation. “If there is legislation, it is often weak and difficult to enforce, so it is becoming an attractive crime,” Clark comments.

What is really needed is a universal outlawing of counterfeit medicines. Narcotics, Clark points out, are internationally recognized as banned substances. “If we can get counterfeit medicines universally recognized as illegal,” Clark says, “then we can build up a global collaborative system.”

"Unique identifiers won’t be the silver bullet to stop counterfeiting, but when you get the rare instance of counterfeit medicines breaching the supply chain, this kind of track-and-trace will be phenomenally helpful."

"Unique identifiers won’t be the silver bullet to stop counterfeiting, but when you get the rare instance of counterfeit medicines breaching the supply chain, this kind of track-and-trace will be phenomenally helpful."